What Do Zambia's Wildlife and Bones Reveal?

11 June 2025

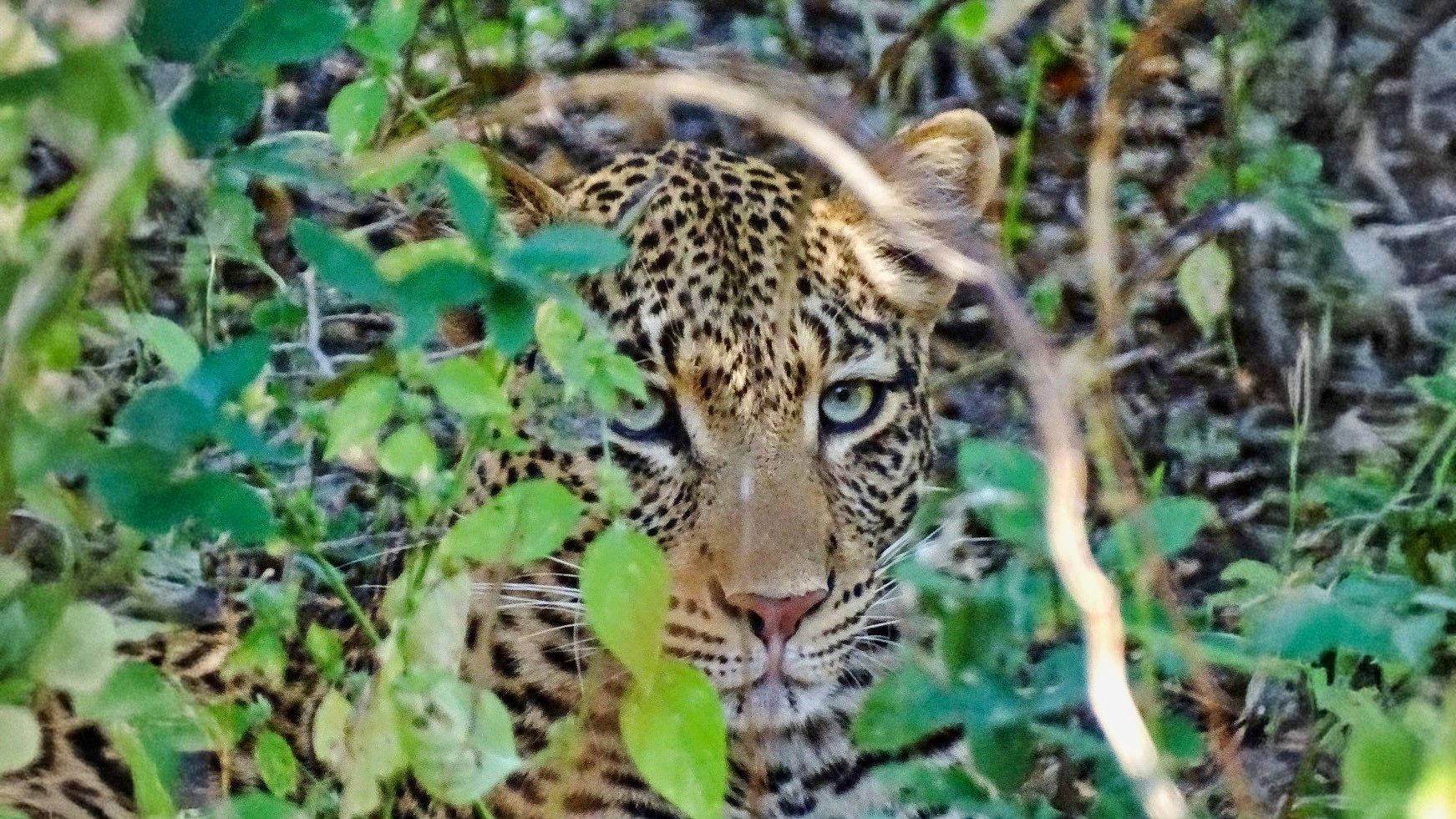

Our own Stan Rullman, PhD., Research Director, travelled to the awe-inspiring South Luangwa National Park in Zambia to take part in the expedition "Wildlife, Bones, and History in Zambia." Stan shares his experience of exploring the park's vast landscapes, uncovering bones along the Luangwa River, and working with Earthwatch volunteers to help inform future conservation efforts in this ecologically vital region.

This 2025 season marks the conclusion of this Earthwatch expedition. With two remaining teams, there is still an opportunity to support one of Africa's most extraordinary wildlife parks alongside dedicated scientists.

One of the first countries Earthwatch supported with on-the-ground research (back in 1971) was the southern African nation of Zambia. And this year, we return for the final two teams to undertake what I consider one of the most quintessential Earthwatch projects in our history. The two principal investigators, Drs. Amy Rector and Thierra Nalley, originally proposed their project to launch in 2021. COVID had other plans. In 2023, I had the pleasure of joining the first team in South Luangwa National Park (now ranked as one of the top 10 wildlife parks in Africa) for ten unforgettable days of fieldwork among some of the planet’s most impressive wildlife.

The scientists’ original proposal included three main components:

What makes this research special is how these three aspects are braided together to help park managers prepare for the impacts of a changing climate in the region—a brilliant example of using the past to understand the future.

The wildlife surveys aim to estimate current populations of large mammals in the park. These driving transects use a technique known as distance sampling, where researchers record the distance and bearing to the animals observed. This detectability factor allows for a more accurate estimate of species populations within the study area.

The second research aspect is palaeontological. Palaeontology—the study of fossilised plants and animals (excluding humans)—has long been part of Earthwatch's research portfolio, though it appears less frequently in recent years. In contrast, archaeology focuses on human remains and artefacts. We occasionally find artefacts dating back to the Iron Age, more than 1,500 years ago.

Fieldwork involves walking the sandy riverbanks to systematically search for bone fragments and, ideally, fossilised specimens that help us understand what past wildlife communities looked like. The goal is to uncover fossils dating from the late Pliocene (3.6 to 2.6 million years ago) to the late Pleistocene (about 125,000 to 11,700 years ago). So far, fossils discovered have not been quite old enough to meet the project’s initial scientific objectives, so this element will not be a focus for the final teams.

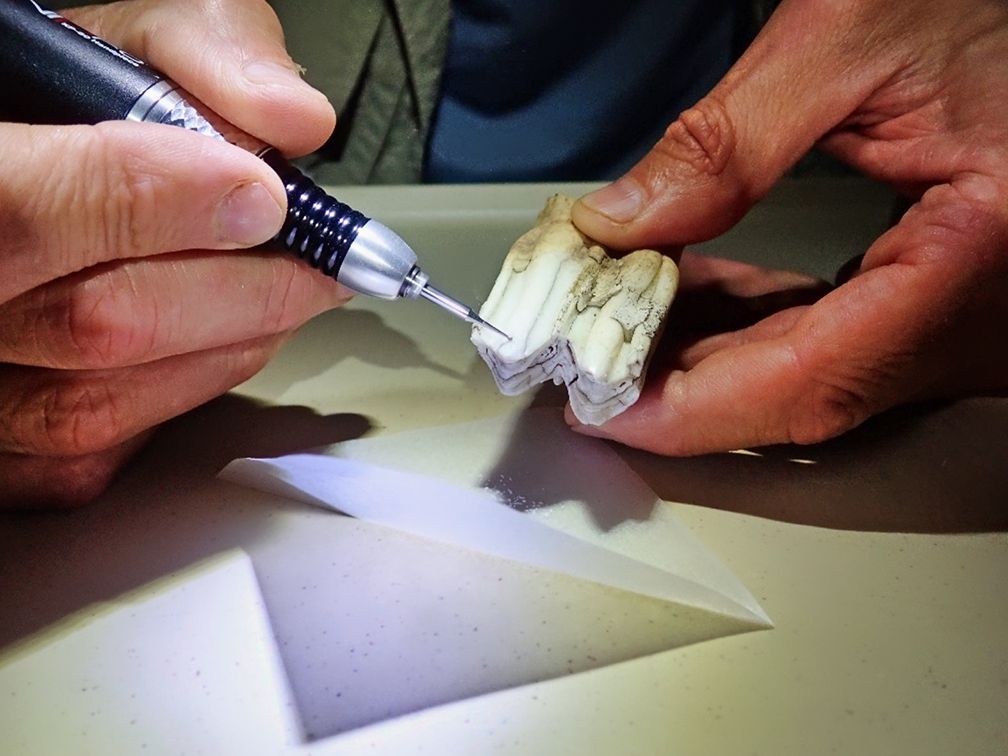

Drawing from previous field studies, the team uses minerals from older teeth and bones to analyse ancient diets through advanced stable isotope analysis. This method helps determine whether wildlife species changed their diets in response to climatic shifts—insights that are crucial for predicting how animals might adapt to modern climate change.

To compare dietary patterns across time, the team also collects newer, non-fossilised bones—often referred to as "prey remains." Using a systematic search method, field teams disembark from vehicles and move in a line through the bush, flanked by a team member and an armed ranger, looking for bones.

Small samples are brought back to base camp, where a makeshift lab in a gazebo allows participants to help process enamel from the bone and tooth fragments. These are then sent to a professional lab in the US for detailed analysis. By comparing carbon and oxygen isotopes in both fossil and modern remains, scientists can assess whether herbivores in the region historically fed more on grasses or on woody vegetation. These findings are vital for understanding how ecological relationships respond to environmental change.

All of this helps park managers better prepare for climatic shifts, including projected rises in temperature, decreases in rainfall, and more extreme weather events. Knowing how species responded to past climatic changes offers invaluable context for managing ecosystems today.

This summer marks the expedition's final season, and the scientists will lead the last two teams in South Luangwa National Park. I would love to see them supported with full teams of ten participants. A few spaces remain for this unique and classic Earthwatch experience in one of Africa’s most exceptional wildlife parks.

Join our newst Africa-based expeditions "Restoring Habitats in Kenya's Greater Maasai Mara", restore Kenya's Greater Maasai Mara Ecosystem through research and conservation

Whether you have a background in science or are simply passionate about protecting our planet, these expeditions provide hands-on experiences that contribute directly to critical environmental research. Participants learn field research techniques, collect valuable data, and gain a deeper understanding of the challenges facing our ecosystems—all while exploring breathtaking natural environments.

By joining an Earthwatch expedition, you can actively contribute to the preservation of coral reefs and other vital ecosystems while being part of a global movement for environmental conservation.

Want to participate in a similar expedition? Get involved today!